Golden Predator Mining Corp. was a publicly traded junior exploration company which operated in Canada’s Yukon. The company was led by Chief Executive Officer, Janet Lee-Sheriff, and Executive Chairman, William M. Sheriff. The Company operated as both a disruptor and innovative in the gold exploration sector and undertook many different and ground-breaking initiatives both with technological developments and community engagement. The focus of this case study is community engagement when the Company chose to be an industry leader and developed an Elder-in-Residence Program at its 3 Aces Project located in the southeast region of the Yukon. The project was in the traditional territory of the Kaska Nation represented by both the Liard First Nation and Ross River Dena Council. The Kaska Nations are indigenous to approx. 240,000km2 spread across the Yukon, Northwest Territories, and British Columbia, where they have hunted and lived off the land throughout history. They thrived within their own society which shared a common culture, language, and law. Much of this society has been damaged and destroyed due to European colonization and there is a great need to preserve and reinforce their way of life while working to advance projects due to a rich mineral base. Their ties to their land and history are very important to acknowledge, especially when modern companies are on their traditional lands for corporate projects.

The relationship between indigenous communities and the corporations working on their traditional territory is, at times, a fragile one that is often overlooked at early-stage projects where economics and future developments are unknown. The relationship between an exploration or mining company and local communities takes time and effort to build and early, and consistent engagement should be implemented. The form of engagement is unique in each community; every indigenous group has different approaches to mineral development, key values, issues, and ways of life, and therefore there is no cookie cutter approach to fostering a successful relationship. CEO Janet Lee-Sheriff already had an extensive 30-year history working alongside the Kaska Nation prior to the 3 Aces project which greatly strengthened her ties to the First Nations and helped develop her respect for the Kaska culture. When Golden Predator began their project at 3 Aces, she took a different approach and began working with the Kaska Nation before work began with the exploration drill program.

At the request of the Chief of the Ross River Dena Council, a prayer ceremony was held on the top of the mountain where the work was to commence. A day of prayer for safety, family and the land left a prayer circle on the mountain to provide greater strength for the project, and people. This act of respect, and a respectful working relationship with mutual benefit, enabled the Company to permit and construct a bridge over Little Nahanni River in 4 months due to the support of the Liard First Nation and Ross River Dena Council. This process would have been considerably more difficult and time consuming had there been a lack of understanding between the Kaska Nation and Golden Predator management. Following this, a drum ceremony was held on the newly built bridge which once again marked their developing alliance. The constant exchange and and acts of respect built the foundation of a strong, united working relationship that proved vital to both the progress of the 3 Aces project as well as the Kaska community.

Along the way, Janet Lee-Sheriff developed a friendship with Mary Caesar, a Kaska Elder, artist, residential school survivor and member of the Liard First Nation. Caesar voiced her concerns regarding the environment and the potential harm that the mining industry can cause to their traditional land. She emphasized the need for the Kaska Nation’s voice to be heard and that their traditional knowledge must be respected and upheld. She was also concerned about mining companies profiting off Indigenous land without the economic benefits being realized locally, and she did not want this to happen to her people and on her land. Janet Lee-Sheriff and Mary Caesar started a regular dialogue about the project which eventually included a site visit and community presentation. To provide the Kaska Nation with immediate economic benefits, Golden Predator initiated a 2% community fee under an Exploration Benefits Agreement, a first in the region. Although Mary appreciated the efforts Golden Predator had made to include the Kaska people, she made it clear that more had to be done to involve the Elders in the project. Elders are vital to indigenous communities: they serve as leaders, teachers, healers, advisors, and counsellors. Furthermore, they are knowledge keepers and ensure cultural continuity. Mary suggested an Elder-in-Residence Program to be implemented on-site at the 3 Aces project, as an innovative way to encourage the sharing of knowledge of Indigenous perspective while building a stronger community relationship. Ms. Lee-Sheriff immediately responded the suggestion was excellent and that the program would be developed in conjunction with the Elders.

Strategy

The initiative began with meetings in both home communities of the Liard First Nation (Watson Lake, Yukon) and the Ross River Dena Council (Ross River, Yukon). The meetings had consistently high attendance, with around 20-25 Elders attending each. It was at these meetings where the Elders shaped the program and in June of 2018, the program

- The program worked directly with Ross River Dena Council and Liard First Nation Elders to support learning and understanding, promote cultural awareness and share wisdom/and teachings as part of the exploration process.

- In total, 4 Elders (2 from Ross River and 2 from Liard First Nation) would reside at 3 Aces at any given time. The Elders-in-Residence stayed for a minimum of one week but were able to be considered for longer stays if desired.

- Two cabins at the 3 Aces Camp with wheelchair access were designated for Elders.

- Travel to and from site, plus all meals, were provided and an honorarium was paid. A Physician’s Assistant was onsite and safety gear was provided.

Elders lived and worked on site for the operating season and were a valuable part of the exploration process. Susan Magun, a Golden Predator employee, and member of the Kaska Nation, played a vital part in the organization of the program, working closely with the Elders from her office in Watson Lake and ensuring the program was smooth sailing. She was a pillar of support for her people and made certain that the Elders were well looked after while considering their needs and potential disabilities. There were no specific requirements as to how the Elders spent their time at camp was spent other than a safety orientation, and they could choose to participate in as little or as much as they wanted. They were incorporated into all aspects of camp life including helicopter tours to view work and spot wildlife, inspecting core samples, watching drill and sample programs, and speaking with all staff. The Elders were encouraged to maintain their Indigenous ways of life on the life, amongst the exploration program, while also being provided with all the tools to understand Golden Predator’s exploration and the various work programs underway at 3 Aces. Golden Predator aimed to be 100% transparent about the work underway and encouraged a candid dialogue between the Kaska Nation and staff, providing answers and explanations to any questions or concerns the Elders may have. Vice versa, the Elders provided Golden Predator staff with the educational tools to understand the Kaska culture, including their traditions, language, and respect of traditional knowledge of the land. The Elders mentored staff and provided guidance, used traditional mediation techniques when necessary, and provided support to all that wanted it. It was a fluid program to allow Elders to draw on their own strengths; each Elder had something unique to contribute to the camp, and this was encouraged. Some pursued traditional medicines while some worked on their sewing or beading. They all enjoyed monitoring wildlife and ensured the state of the land remained unharmed. Although flexible, some of their everyday duties and responsibilities could include:

- Assist with mentoring staff and providing guidance, counselling youth and acting as mediators in conflict resolution and healthy life styles;

- Be a contact for a healthy lifestyle outside of camp life;

- Providing management and supervisors with mediation skills and guidance to better assist staff at site;

- Consider future training needs for workplace participation;

- Tour general area – by air (if comfortable) and vehicle to better understand work programs;

- Assist management with guidelines for operations and policies for wildlife management, environmental practices, reclamation, etc;

- Provide staff and management with a better understanding of the Kaska culture, including language and culture;

- Participate in traditional activities including harvesting berries, medicines and plant identification (hunting was not permitted while staying camp due to safety guidelines);

- Where comfortable and permissions in place provide traditional knowledge as appropriate. This could include traditional and historic use of the land, customs and traditions;

- Uphold the spiritual connection to the land and provide spiritual guidance where comfortable.

Impact & Points of Learning

Initially, there were some concerns over the program and the possible distractions and increased workload it could bring the project. Despite these worries, the Elders program was a great success and surpassed the expectations of both the Kaska Elders and the staff and management of Golden Predator Mining Corp. There was overwhelmingly positive feedback regarding the program: staff appreciated the wisdom and life experience that the Elders shared, and the Elders appreciated the staff’s eagerness to understand their culture and respect their traditional land. The Elders improved camp life and benefitted the program in many ways, making camp feel more like a home environment with a nurturing and supportive dynamic. Similarly, the Elders enjoyed seeing the younger generation hard at work which brought them a sense of pride and purpose. Education is a two-way street, and both the Elders and the Golden Predator staff had a lot to learn from each other. By involving Elders in all aspects of the project, Golden Predator staff learned traditional Kaska knowledge that proved beneficial in various situations, and they developed a deep respect for their culture. Golden Predator was able to educate the Elders about their work programs and teach them their philosophies, allowing the Kaska Dena First Nations to benefit from the mining sector while overseeing environmental policies of their land. The program offered a non-political way to engage the community and understand world view and experience and it proved that concerns in exploration and mining activity can be managed with respect and approach. The program provided a platform for voices to be heard and stories to be shared regarding a wide variety of topics, from traditional medicine to colonial issues such as residential schools and their lasting consequences. The issues that could have divided the two groups instead united them and provided an exciting new future. There was an ongoing exchange of information and a newfound shared appreciation for concerns on culture, wildlife, environment, revenue sharing and mine development. The impact of the Elder-in-Residence Program had rippling effects within the community which proved the program’s value and demonstrated that there is space for everyone in the sector: Elders, youth, men and women. Some notable achievements included:

- A total of 55 Elders participated in the program throughout 2018;

- Kaska youth were surrounded by opportunities in the mining industry which provided valuable progress and potential for their economy and community;

- Women played a vital role in camp life, becoming leaders in the sector much like their traditional Kaska Dena roles;

- Kaska Dena mediation techniques in the form of a healing circle were utilized when two staff members had trouble working together and the Elders provided ongoing support throughout the operating season;

- Staff retention was over 90% in 2018, directly attributed to the Elders presence in the camp;

- Enhanced Human Resources & Camp Health: when much of the camp fell ill to the flu and traditional Kaska medicine was used to relieve symptoms and speed up recovery;

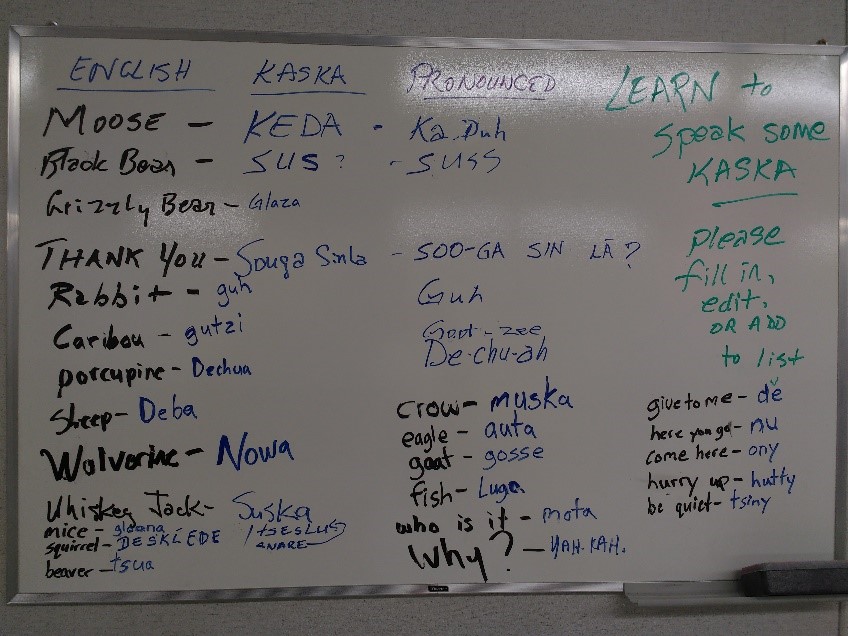

- A Kaska language component was incorporated to the programs and all wildlife monitoring was tracked in the Dene language. Language classes became part of camp life;

- The creation of two videos to allow both the Ross River Dena Council and Liard First Nation Elders to have their voice heard;

- New potential to do business together and build the community’s economy and prosperity.

The success and potential future of the program raised the critical point of involving the youth more in the mining sector. One key issue consistently mentioned by Elders throughout the duration of the program were the negative consequences of the residential schools, and the impact they continue to have on current generations of youth. The Elders emphasized a need for dramatic changes to stop the cycle of generational trauma and create a better community for their children. These changes would include a healthy lifestyle, more opportunities for jobs and careers, and a major increase in support and guidance. With the mining sector being constantly present in many of these regions, there is a need to educate youth and encourage them to build careers in the sector. By doing so, the mining sector can help reduce some of the generational trauma caused by colonialism while enhancing the prosperity and economic development of these communities. As a response to this, a two-day Summit was held at the end of the operating season with a total of 80 Kaska people and youth in attendance. It was a great opportunity for everyone to get together and discuss a variety of topics, and it provided a chance for youth to get familiar with the mining sector and camp life. Furthermore, it allowed an open discussion concerning the Elders-in-Residence Program: what worked, what didn’t work, and what could be improved for the next operating season. The Summit allowed the Kaska Nation to pave a path forward, which focused on the involvement of Kaska.

Kaska Dena Elder Mary Caeser went on to win the Indigenous Innovator Award from Women in Mining Canada. Caesar, a residential school survivor, credits the Kaska culture instilled in her from her elders for her survival and ability to thrive in the face of diversity. Her values were directly embodied in the program and as a result, have united the mining sector and the Kaska community to work together for a bright future. She has proven that mutually beneficial relationships can be cultivated, appreciated, and can create strong community bonds in which everyone is heard, respected and given the tools to succeed. The Elders Program would not have happened without her and her achievements received widespread international recognition at PDAC, the biggest mining conference in the world.

Path forward & Key Messages

Unfortunately, the Elders-in- Residence program did not continue as Golden Predator merged with Sabre Gold, and the 3 Aces project was ultimately sold to another company. Despite this, the program showed how valuable it is to initiate a relationship with the indigenous community you are working with. The issues that could have divided the two groups instead united them and provided an exciting new future. Golden Predator’s former management has taken this valuable experience and continues to apply it in their current projects throughout North America. Although the Elders-in-Residence program was a success, its success was dependent on many factors. Each First Nation community is unique in its own ways, and there will be a variety of approaches needed to initiate further working relationships. As was done with the Kaska Nation, it is crucial to listen to what each community has to say and to mutually agree on an effective program since there is no cookie cutter approach. Connecting with the people on a micro-level as opposed to a macro-level is fundamental to understanding community issues from a bottom-up approach which as a result, can aid in developing a plan that benefits those that need it the most. In other words, listening to local citizens and allowing anyone to express their opinions and views will allow you to see a fuller picture of the societal issues at play. The involvement of youth remains a key point in many of these communities. Companies bringing their corporate projects onto the lands of indigenous nations must provide nearby communities with not only jobs, but also with proper education for them to succeed in these jobs, along with ongoing support, business development and other opportunities. The path forward for corporations working in Indigenous communities remains a rocky one, with lots of factors at play and lots of improvements to be made. However, the Elders-in-Residence program is a success story that proves that there are unique and successful approaches to fostering relationships if the corporations are willing to listen and take the time.